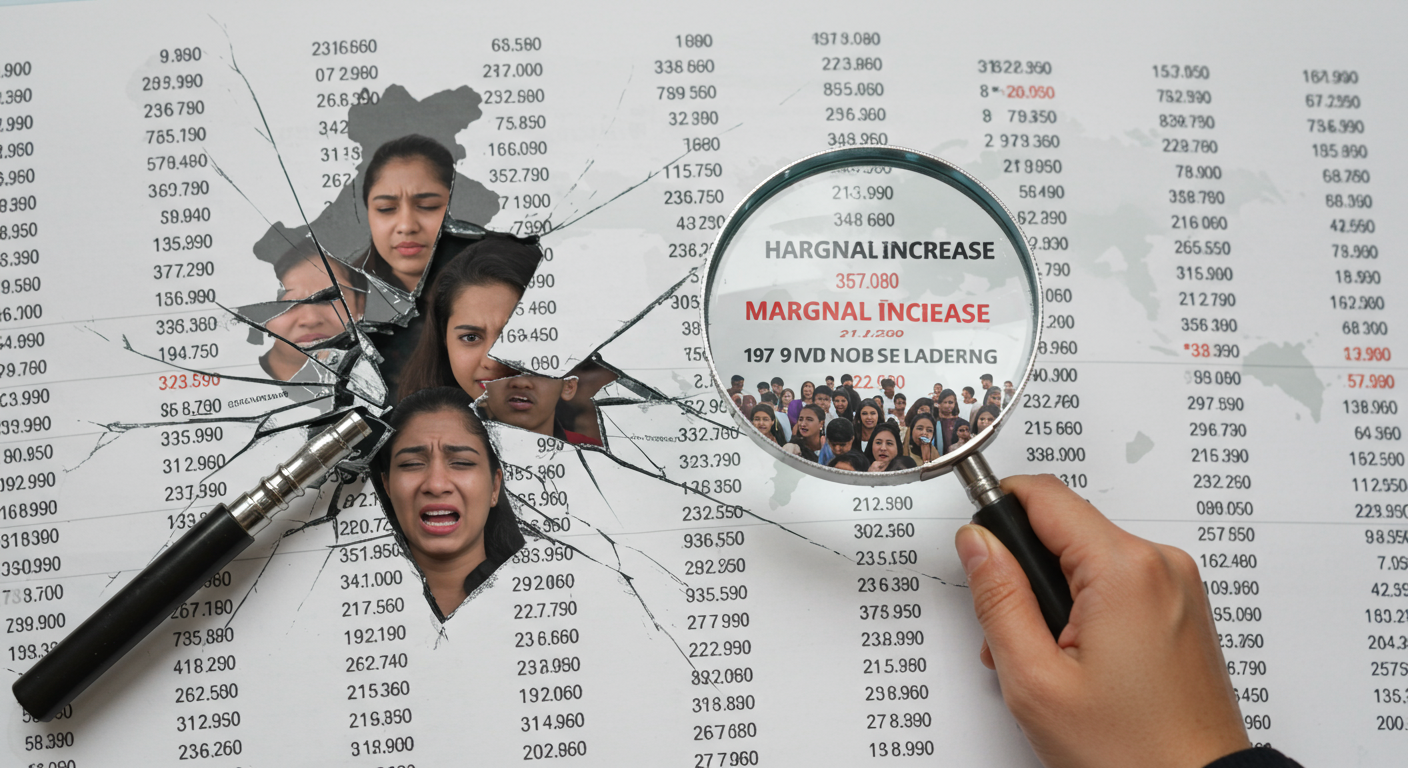

The recent analysis from CJP, titled "When ‘Marginal’ Means Massive: The invisible weight of gendered violence in NCRB crime statistics 2023" When ‘Marginal’ Means Massive, compels a deeper look into how we perceive and address violence against women and children in India. The article powerfully highlights that what appears as a "marginal" increase in official statistics translates into a massive, heartbreaking reality for tens of thousands of survivors.

The Illusion of Numerical Comfort

When I read that India recorded 471,000 reports of crimes against women in 2023, a nominal increase of three percent, my mind immediately went back to my earlier reflections. Years ago, I wrote about how "Crimes… must be deplored, irrespective of where/when they take place" NO ONE’S MONOPOLY !. The language of percentages in the NCRB report often creates a deceptive sense of stability, a bureaucratic comfort that masks the true scale of suffering. A three percent rise is not marginal when it means over 14,000 more women reporting violence, as the CJP Team rightly points out. For children, the situation is even more dire, with POCSO cases increasing by 9.2%, exceeding 170,000. These are not mere data fluctuations; they are lives irrevocably altered.

Faces Behind the Figures

The article brought to light the tragic story of Reena Joshi, a 26-year-old married woman from Dewas, Madhya Pradesh, who died after alleged harassment by Zakir Hussain. Despite multiple complaints to the local police, no preventive measures were taken. This case tragically illustrates how everyday harassment can escalate into fatal violence, and how the legal system often responds after a life is lost, sometimes minimizing the gendered and communal motivations. On August 16, 2023, Jayanta Roy (jayanta@thesecretariat.in), a 35-year-old resident of Zamindar Para in Jalpaiguri, threw acid on a 22-year-old woman for rejecting his advances. This act of violence followed weeks of trailing and harassment, and despite family reports to the police, initial action was rebuffed as a "personal dispute." These incidents, along with the critical legal research team at CJP, including Preksha Bothara, highlight the systemic failures. This resonates deeply with my past concerns about police accountability and understaffing, which I discussed in my blogs, "WHO WILL INVESTIGATE POLICE BRUTALITIES ?" and another from the same period, where I shared NCRB findings on complaints against police and the inadequate police-to-population ratios in various states. The structural neglect and inaction highlighted by the CJP report against such a backdrop is a stark reminder of persistent challenges in our law enforcement.

The Erasure of Identity and Experience

One of the most profound critiques in the CJP article is how NCRB's categories flatten the identities of victims. Crimes against women are presented without disaggregating for caste, religion, class, or disability, which are crucial factors in vulnerability and access to justice. This structural erasure, as feminist scholars term it, blinds us to intersectional violence. The Hathras case (2020) is a chilling example where a Dalit woman's rape was ignored and erased—a trend that NCRB's data design continues to obscure.

Furthermore, the gender binary in the Bureau's data completely erases LGBT survivors, including trans women and gender non-conforming people, making their experiences invisible. This is not just a statistical oversight; it's a reproduction of harm through the guise of neutrality.

Acid Violence: A Case Study in Indifference

West Bengal emerges as an epicenter of acid attacks, accounting for nearly one-fifth of all reported cases in India in 2023. The stories of survivors—transported between ill-equipped hospitals, facing years-long court delays, or falling into poverty awaiting mandated compensation—are heart-wrenching. The classification of acid attacks under a neutral "grievous hurt" rather than targeted misogynist violence diminishes its symbolic and social identity. Organizations like Acid Survivors Foundation India (ASFI) have consistently highlighted how police often evade proper IPC sections (326A, 326B) to suppress crime rates, creating a cycle of denial within NCRB records.

The Cost of Systemic Erasure

The article underscores that pending cases, lengthy trial times (averaging over 5 years), and woefully underfunded One-Stop Centres further exacerbate the crisis. Even in digital spaces, new forms of gendered violence like online stalking often escape a proper gendered lens, framed instead as 'defamation' or 'obscenity'. This structural undercount, CJP argues, is a "performance of stability," designed to present a calm façade while the continuum of harm remains intact. To genuinely understand gendered violence in India, we must look beyond the numbers, into the silence and the omissions.

Regards,

Hemen Parekh

Of course, if you wish, you can debate this topic with my Virtual Avatar at : hemenparekh.ai

No comments:

Post a Comment