I’m cautiously optimistic: more doctors are coming

Over the last decade I’ve watched India’s medical-education ecosystem change faster than I expected. By 2024 the country had substantially expanded MBBS capacity, and policy reform—paired with changes to regulation and international pipelines—means India is poised to produce many more doctors than earlier forecasts implied. That is good news, but it is not the whole story. We need to be clear-eyed about what this means for access, quality and costs.

What changed — the main drivers

Policy-driven seat expansion. The central push to create medical colleges by upgrading district/referral hospitals and schemes under PMSSY and other centrally-supported programmes materially increased undergraduate and postgraduate seats. This expansion has been a deliberate, multi-year programme to add college capacity where possible Lok Sabha reply, Aug 2024.

Regulatory reforms. The National Medical Commission (NMC) replaced the older regulator and simplified approvals and frameworks for adding seats. The NMC also published draft and final regulations around the National Exit Test (NExT) and Minimum Standard Requirements that change how foreign-trained and domestic graduates are certified and counted for practice and PG admissions NExT draft / regulations, NMC public notice.

Foreign-trained doctors and screening changes. For years many Indians trained abroad (China, Eastern Europe, Bangladesh, Nepal, etc.). Policy shifts around a unified exit/screening exam (NExT) and clearer recognition pathways mean a more predictable inflow of foreign-trained graduates who can practise in India after clearing licensure requirements.

Private sector and academic growth. A large share of new seats has come from private and deemed institutions, adding capacity quickly but also raising debates about costs and standardisation.

Recent context and numbers (to anchor the argument)

Registered allopathic doctors numbered around 1.38 million (13.86 lakh) as of mid-2024; using conservative availability assumptions the government reported a doctor-population ratio that year around 1:836—better than the oft-cited 1:1,000 WHO benchmark Lok Sabha reply, Aug 2024.

Seat expansion has been rapid, but not frictionless: official data presented in 2024 showed thousands of new MBBS seats, yet several hundred to a few thousand undergraduate seats remained unfilled in 2024 across institutions — a reminder that adding capacity does not automatically convert to immediate trained clinicians available in-service Indian Express report on vacant seats, 2024.

NExT and related regulations (published in draft/final forms in 2022–2023) seek to standardise entry-to-practice and PG allocation; rollout timing and practicalities were still in transition in 2024 and required phased implementation and mock runs to avoid disruption.

Potential impacts — positive and cautionary

Positive effects

- Greater supply should ease long-term shortages in absolute numbers and improve national metrics (doctors per 1,000 people).

- Increased PG seats over time could reduce the bottleneck for specialisation and keep more doctors in India instead of seeking foreign training.

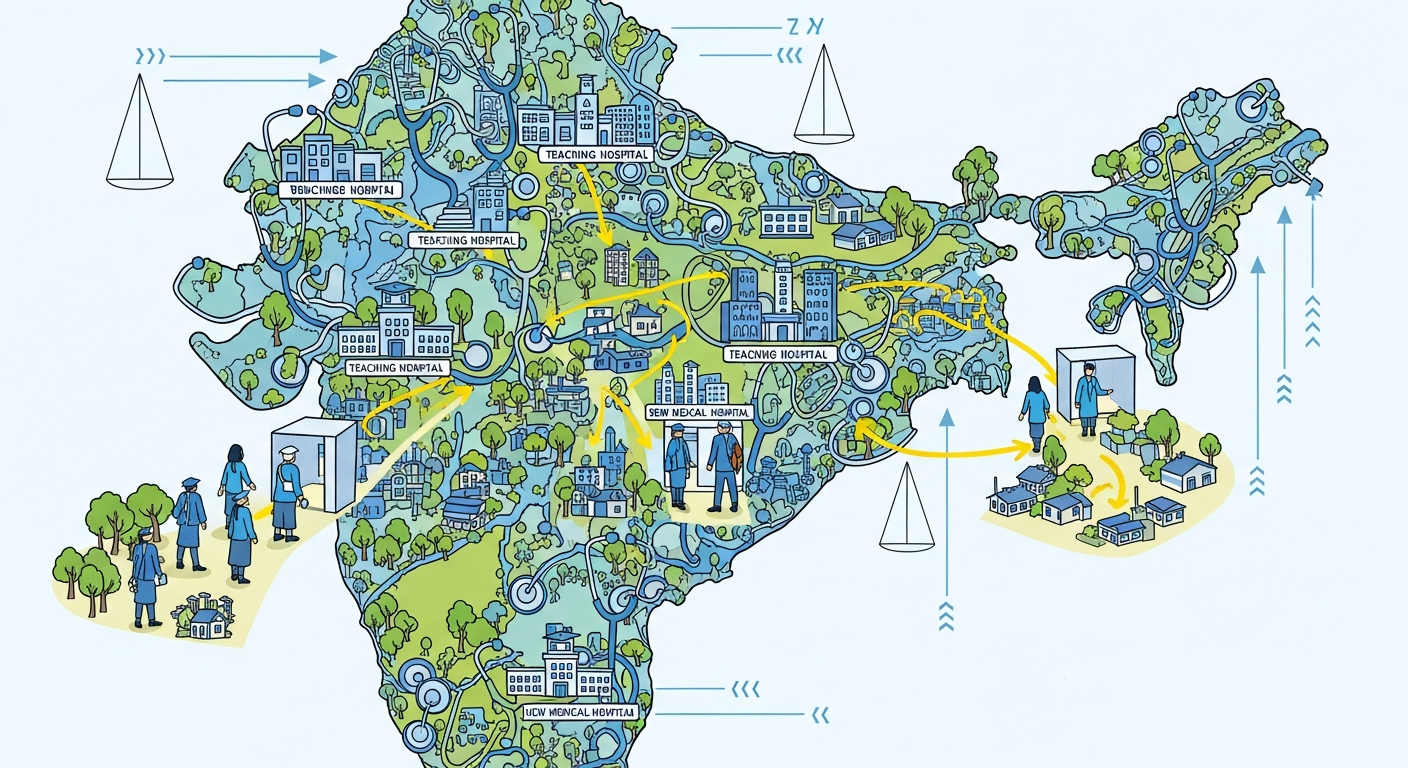

- More medical colleges in smaller cities can create local hubs of clinical care and teaching hospitals, improving tertiary referral capacity.

Caveats and risks

- Distribution remains the central problem. Urban centres attract most clinicians; rural and tribal districts often remain underserviced despite national seat increases.

- Quality varies. Rapid private-sector expansion and hurried upgradation of facilities can create institutions with weak clinical exposure or faculty shortages.

- Costs may rise for students in private settings; that can shape future practice choices (doctors under high debt may prefer high-fee urban jobs over rural postings).

Key challenges to turning seats into better care

- Quality control and faculty: new colleges need experienced teachers, enough clinical material (patient load) and functioning labs. Minimum standards help, but enforcement and faculty pipelines are essential.

- Distribution and retention: posting new graduates to districts is not enough; retention requires career incentives, living conditions, schooling for children, and clear career paths.

- Infrastructure and systems: PHCs, CHCs and district hospitals need sustained investment in diagnostics, supplies, referral networks and telemedicine.

- Regulatory transition: moving to NExT or other unified licensure must avoid sudden shocks (example: backlog of interns, timing mismatches between exams and internships).

Practical recommendations I’d make

- Strengthen rural incentive architecture

- Meaningful financial plus career incentives (accelerated PG seats, higher pay, housing, spouse employment support) for multi-year rural service.

- Protect and grow faculty capacity

- Fast-track fellowships, DNB/MD clinical teaching tracks, visiting faculty fellowships and digital bedside-teaching networks linking new colleges to established centres.

- Tie seat expansion to enforceable quality milestones

- Conditional LOPs: seat increases phased with audits of patient load, lab capacity, and faculty retention metrics.

- Expand internship capacity and district residencies

- Create paid, supervised district-residency posts for interns/PG residents to ensure skills and improve local services.

- Use technology to rebalance access

- National telemedicine hubs, supervised tele-mentoring for rural doctors and AI-assisted triage to extend specialist reach.

- Make licensure transitions predictable

- If a national exit test (NExT) is adopted, run transparent mock cycles, publish timetables and allow bridge measures so foreign-trained and domestic graduates aren’t left in limbo.

Final thought

More doctors are coming—and that is worth celebrating. But numbers on paper are only a first step. If India wants that surge to translate into earlier diagnoses, fewer referrals, lower out-of-pocket costs and stronger primary care, we must pair capacity with the right incentives, enforcement and infrastructure. I remain hopeful because the levers exist; we must now choose the political will and policy detail to pull them.

Regards,

Hemen Parekh

Any questions / doubts / clarifications regarding this blog? Just ask (by typing or talking) my Virtual Avatar on the website embedded below. Then "Share" that to your friend on WhatsApp.

Get correct answer to any question asked by Shri Amitabh Bachchan on Kaun Banega Crorepati, faster than any contestant

Hello Candidates :

- For UPSC – IAS – IPS – IFS etc., exams, you must prepare to answer, essay type questions which test your General Knowledge / Sensitivity of current events

- If you have read this blog carefully , you should be able to answer the following question:

- Need help ? No problem . Following are two AI AGENTS where we have PRE-LOADED this question in their respective Question Boxes . All that you have to do is just click SUBMIT

- www.HemenParekh.ai { a SLM , powered by my own Digital Content of more than 50,000 + documents, written by me over past 60 years of my professional career }

- www.IndiaAGI.ai { a consortium of 3 LLMs which debate and deliver a CONSENSUS answer – and each gives its own answer as well ! }

- It is up to you to decide which answer is more comprehensive / nuanced ( For sheer amazement, click both SUBMIT buttons quickly, one after another ) Then share any answer with yourself / your friends ( using WhatsApp / Email ). Nothing stops you from submitting ( just copy / paste from your resource ), all those questions from last year’s UPSC exam paper as well !

- May be there are other online resources which too provide you answers to UPSC “ General Knowledge “ questions but only I provide you in 26 languages !

No comments:

Post a Comment