Summary (2–3 lines)

The rural jobs programme is showing a curious disconnect: reported person‑days of work have risen in some periods while central spending appears constrained. In this post I explain how that can happen, what it means for rural households and local economies, and what policy choices would protect vulnerable families.

Connect with me: Hemen Parekh (hcp@recruitguru.com)

Why this matters to me — and to rural India

I write about public policy because ideas on paper often meet very different realities on the ground. A scheme that promises work and steady wages becomes a lifeline for millions — and when the lifeline frays the effects ripple through villages, towns and markets. I have written about expanding and rethinking rural guarantees before (How about asking URBAN poor?). That thread — protecting incomes and thinking systemically — guides what follows.

The basic puzzle: more workdays, less central spending

At first glance the idea that workdays can increase while Centre spending declines looks impossible. But several mechanisms — administrative, accounting and policy — can produce exactly that appearance:

Lower real wages or frozen nominal wages. If the rate paid per person‑day is not increased in line with inflation, the same or even larger number of person‑days will cost less in real terms. Nominal freezes make central outlays buy less.

Shifts in cost composition. Central budgets historically covered 100% of unskilled wages and a large share of material/admin costs. If the funding pattern or cost‑sharing shifts (for example, more material/admin burden on states), the Centre’s cash outflow falls even if total scheme spending (centre + state) remains unchanged.

Lower material/contract costs. If states choose cheaper materials or fewer high‑cost assets, the material share of spending falls. That reduces central releases if the Centre pays a share only of material budgets.

Accounting, timing and backlog effects. Governments operate with allocations, releases and recorded expenditure. A Centre may reduce releases or delay them, creating unpaid liabilities that show up as arrears rather than current spending. Conversely, work done earlier may be paid later and counted in a different fiscal period.

Allocation ceilings versus actual demand. The Centre sets labour budgets (person‑day ceilings) and cash ceilings. If states run up workdays within their own funds or by reprioritising, person‑days can tick up even as central transfers are constrained.

State‑level financing and substituting funds. Some states choose to top up the scheme from their own budgets — especially richer or politically committed states — causing higher person‑days with less marginal central spending.

Supply‑driven planning vs demand‑driven entitlement. If programme design moves from demand‑led (workers ask for work) to a supply/planned model (pre‑approved works), the number of reported person‑days can be manipulated through project scheduling even while cash flows are restricted.

How these mechanisms play out: concrete examples

A village gets more short‑duration tasks (e.g., seeding, small repairs) at the existing daily wage; person‑days rise but the average daily cost (including materials) falls — the Centre’s per‑day liability declines.

A state absorbs material costs using local procurement or budget headroom. The Centre records lower releases for materials even as the actual work continues.

The Centre asks states to limit releases in the first half of a year (cash‑flow management), so states shift to wage payments from local contingency funds; central outlays look lower until reconciled later.

(Where I’ve seen similar tensions in commentary and data: analyses by civil‑society trackers and press reporting have documented mismatch between allocations, releases and person‑days in recent years.)

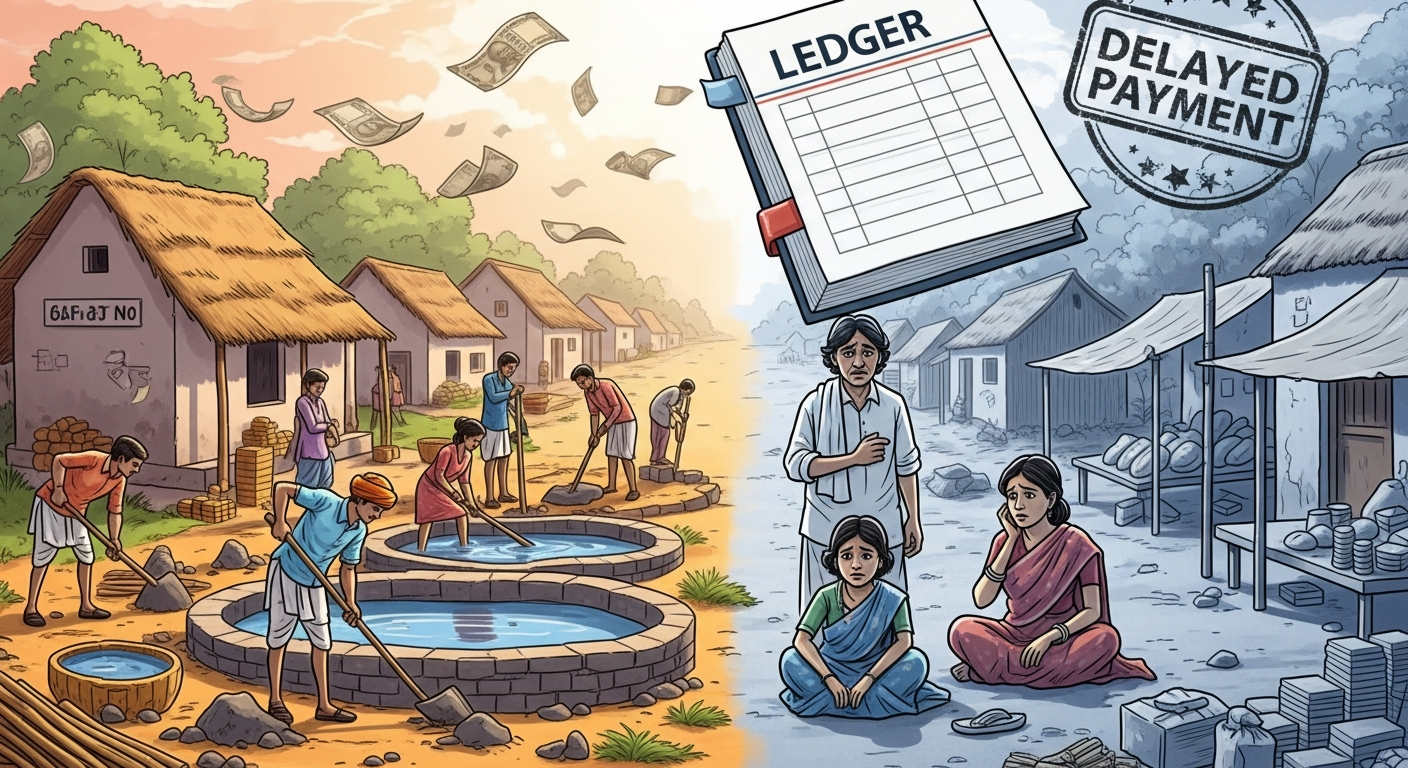

Implications for rural households and local economies

Income uncertainty. Even if person‑days increase on paper, delays in wage payments or lower real wages squeeze household budgets. For poor families that rely on every rupee to buy food and school supplies, timing matters as much as totals.

Crowd‑out of private demand. MGNREGA‑type wages support local retail trade, transport and food vendors; reduced central spending can translate rapidly into lower village demand and slower multiplier effects.

Erosion of the guarantee. If the scheme shifts from an enforceable right to an administratively capped programme, worker bargaining power falls. That harms women (who account for a large share of person‑days) and marginalised households.

Asset quality risks. Pressure to meet person‑day targets with constrained budgets may produce low‑quality assets — shallow waterworks, poorly finished roads — reducing long‑run benefits for agriculture and resilience.

Why might governments do this?

Fiscal discipline. Central government faces deficit targets and competing priorities; controlling releases is a lever for macro management.

Political trade‑offs. A headline of more guaranteed days (e.g., raising the statutory cap) looks good politically even if operational funding is confined.

Decentralisation of cost. Shifting material/admin shares to states reduces Centre’s visible spending while signalling state responsibility — but it burdens poorer states.

Administrative control and targeting. Reworking the scheme toward planned, pre‑approved works lets the Centre target national priorities (water, climate resilience) — at the cost of local demand responsiveness.

Policy recommendations — protect workers, preserve the guarantee

Ring‑fence wages: Centre should continue to fund 100% of unskilled wages (or make clear rules if changed), and index wages to an appropriate rural CPI so real pay is maintained.

Timely automatic releases: introduce trigger‑based releases (linked to verified person‑days) and a short, automatic contingency top‑up to avoid payment delays.

Transparent accounting: publish allocation → release → actual expenditure reconciliations monthly at state level so unpaid liabilities are visible and actionable.

Protect the demand principle: retain a demand‑driven entitlement. Pre‑planned works are valuable, but they must complement — not replace — the right to ask for work.

Equity in cost‑sharing: if cost‑sharing changes, poorer states need compensatory transfers or a sliding cost‑share to avoid austerity‑induced rationing.

Quality safeguards: require geo‑tagged, time‑stamped evidence and third‑party social audits for high‑value works to preserve asset quality while containing cost overruns.

Short‑term income support for gaps: when payments are delayed, an interim cash transfer (small, fast) can prevent consumption shocks among the most vulnerable.

Data sources to watch

- The official NREGA MIS (nrega.nic.in) for person‑day, job‑card and work data.

- Ministry of Rural Development releases and Rajya Sabha / Lok Sabha written replies for allocation and pending liability numbers.

- Civil society trackers (e.g., LibTech India, PRS, Centre for Policy Research summaries) for independent analyses.

- State budget documents and audited accounts for state‑level contributions.

(If you’re trying to reconcile numbers, look for differences between “allocated”, “released” and “expenditure recorded” lines — the gaps tell the story.)

Final thought

Work guarantees are more than ledger entries: they are promises to households that a job and payment will be there when crops fail, markets slow or a seasonal lean hits. The optics of “more workdays” are good — but not a substitute for timely pay, fair wages and durable assets. The policy choice is clear: if we care about rural resilience, the programme must be funded and executed in a way that protects incomes first, assets second.

Regards,

Hemen Parekh

Any questions / doubts / clarifications regarding this blog? Just ask (by typing or talking) my Virtual Avatar on the website embedded below. Then "Share" that to your friend on WhatsApp.

Get correct answer to any question asked by Shri Amitabh Bachchan on Kaun Banega Crorepati, faster than any contestant

Hello Candidates :

- For UPSC – IAS – IPS – IFS etc., exams, you must prepare to answer, essay type questions which test your General Knowledge / Sensitivity of current events

- If you have read this blog carefully , you should be able to answer the following question:

- Need help ? No problem . Following are two AI AGENTS where we have PRE-LOADED this question in their respective Question Boxes . All that you have to do is just click SUBMIT

- www.HemenParekh.ai { a SLM , powered by my own Digital Content of more than 50,000 + documents, written by me over past 60 years of my professional career }

- www.IndiaAGI.ai { a consortium of 3 LLMs which debate and deliver a CONSENSUS answer – and each gives its own answer as well ! }

- It is up to you to decide which answer is more comprehensive / nuanced ( For sheer amazement, click both SUBMIT buttons quickly, one after another ) Then share any answer with yourself / your friends ( using WhatsApp / Email ). Nothing stops you from submitting ( just copy / paste from your resource ), all those questions from last year’s UPSC exam paper as well !

- May be there are other online resources which too provide you answers to UPSC “ General Knowledge “ questions but only I provide you in 26 languages !

No comments:

Post a Comment