Opening

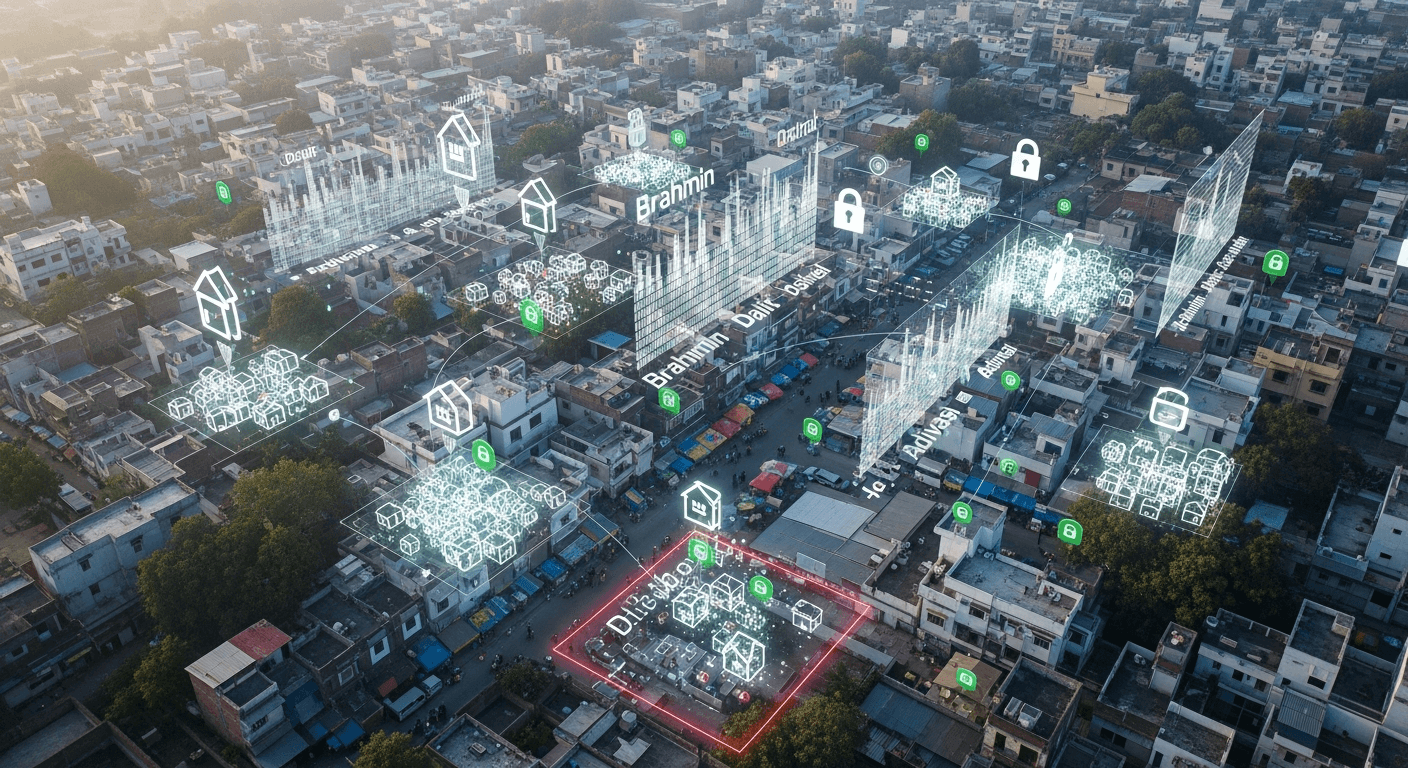

I write this as someone who believes good data strengthens democracy. The decision to include caste details in Census 2027 — alongside the first fully digital house-listing and enumeration — is a watershed moment for Indian public policy and social justice. It can illuminate structural inequalities long hidden by aggregated statistics, but only if the exercise is designed and implemented with rigor, transparency and respect for privacy.

Background: how we arrived here

India last attempted a full caste enumeration in the 1930s; since independence the census recorded Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST) but not a comprehensive caste list. The Socio‑Economic and Caste Census (SECC) of 2011 collected caste-related information but its caste outputs were never fully published for reasons of data quality and methodology. After years of state-level caste surveys and public debate, the Centre has confirmed that caste enumeration will form part of the 2027 national census, conducted in two phases and delivered digitally 2027 census of India - Wikipedia and reporting milestones and timelines Hindustan Times.

Why caste details matter for policy and justice

Caste remains a primary axis of inequality in India, affecting access to education, employment, land, housing, and political power. Granular caste data allows:

- Better targeting of welfare and affirmative-action programmes;

- Evidence-based assessment of which communities remain deprived across states and districts;

- More robust planning for entitlements tied to historical disadvantage;

- Research into mobility, inter-generational change and regional disparities.

Without up-to-date, nationwide caste data, policymakers rely on fragmented surveys or dated proxies, limiting the ability to design or evaluate corrective interventions.

What the household (house‑listing) phase will capture

The 2027 exercise is split into a house‑listing phase and a population enumeration phase. For household-level information relevant to caste analysis, the house‑listing phase is expected to record:

- Household identifiers and dwelling characteristics (construction, amenities, ownership);

- Head of household details and the household’s declaration of social group (SC/ST/Other);

- Basic household-level socio‑economic indicators (to link living conditions with social identity) such as access to water, sanitation, electricity, and asset ownership;

- Linkages to individual-level variables later collected (religion, mother tongue, education, occupation) during enumeration so caste can be analyzed with other outcomes.

The population enumeration phase will collect individual particulars including caste (detailed caste names/sub‑castes), religion, mother tongue and socio‑economic markers — enabling cross‑tabulation at individual and household levels NDTV.

Data privacy, consent and ethical concerns

Collecting caste as a sensitive personal attribute raises legitimate privacy and consent issues, heightened by the 2027 census’s digital approach. Key concerns include:

- Informed consent and clarity about how data will be used, shared and published;

- Secure transmission and storage of sensitive data, with strong encryption, strict access controls and independent audits;

- Risks of linkage with other identity databases (Aadhaar, NPR) that might enable surveillance or exclusion if safeguards fail;

- Digital divide and exclusions if self‑enumeration or online options are used without adequate offline support.

Civil society and data‑privacy experts have warned against rushed digitalisation without robust protection frameworks and transparency measures The News Minute.

Possible benefits and risks

Benefits:

A complete, comparable and geographically granular dataset for inclusive policy design;

Evidence to revisit reservation allocations, entitlements and targeted schemes where warranted;

Strengthened research capacity to study caste dynamics across time and space.

Risks:

Misuse or politicisation of data if release protocols are opaque;

Data breaches or improper linkage leading to discrimination or targeted harassment;

Poor question design or enumerator training creating unreliable or non‑comparable caste entries;

Widening of exclusion if digital mechanisms disadvantage marginalised households.

Recommendations for implementation

To realise benefits while managing risks, I recommend the following practical steps:

- Enumerator training: intensive, contextualised training on caste questions, neutrality, and recording standards; spot quality audits in the field.

- Clear definitions and a validated caste list: publish the methodology for recording caste names and sub‑castes, with protocols for spelling, standardisation and de‑duplication.

- Public communication: a nationwide information campaign explaining purpose, safeguards, consent rights and how aggregated outputs will be used.

- Data protection: end‑to‑end encryption, limited retention for identifiers, role‑based access, and third‑party security audits; publish a transparent data‑release policy.

- Use of unique household/person IDs for safe linkage: enable policy-relevant cross‑tabulations without exposing raw identifiers in public releases.

- Independent oversight: a technical advisory committee with statisticians, legal experts and civil society to oversee methodology, privacy and publication.

Reactions from stakeholders

Responses have ranged from support to caution. States and policy advocates seeking better targeting have welcomed the move; researchers and rights groups stress the need for methodological rigour and privacy safeguards. Political debates will be inevitable, but technical clarity and transparent governance can reduce misinformation and mistrust.

Conclusion: significance and next steps

Counting caste in Census 2027 can supply the missing evidence India needs to diagnose and address long‑standing inequalities. But data alone will not heal historical injustice — it must be accompanied by transparent publication, careful analysis, and political will to act on findings. The immediate next steps are finalising question design, rigorous pilot testing, public outreach, and implementing robust privacy protections. If these are prioritised, the census can be a turning point: a rigorous foundation for more equitable policy and an honest engagement with India’s social reality.

Regards,

Hemen Parekh

Any questions / doubts / clarifications regarding this blog? Just ask (by typing or talking) my Virtual Avatar on the website embedded below. Then "Share" that to your friend on WhatsApp.

Get correct answer to any question asked by Shri Amitabh Bachchan on Kaun Banega Crorepati, faster than any contestant

Hello Candidates :

- For UPSC – IAS – IPS – IFS etc., exams, you must prepare to answer, essay type questions which test your General Knowledge / Sensitivity of current events

- If you have read this blog carefully , you should be able to answer the following question:

- Need help ? No problem . Following are two AI AGENTS where we have PRE-LOADED this question in their respective Question Boxes . All that you have to do is just click SUBMIT

- www.HemenParekh.ai { a SLM , powered by my own Digital Content of more than 50,000 + documents, written by me over past 60 years of my professional career }

- www.IndiaAGI.ai { a consortium of 3 LLMs which debate and deliver a CONSENSUS answer – and each gives its own answer as well ! }

- It is up to you to decide which answer is more comprehensive / nuanced ( For sheer amazement, click both SUBMIT buttons quickly, one after another ) Then share any answer with yourself / your friends ( using WhatsApp / Email ). Nothing stops you from submitting ( just copy / paste from your resource ), all those questions from last year’s UPSC exam paper as well !

- May be there are other online resources which too provide you answers to UPSC “ General Knowledge “ questions but only I provide you in 26 languages !

No comments:

Post a Comment