DDLJ at 30

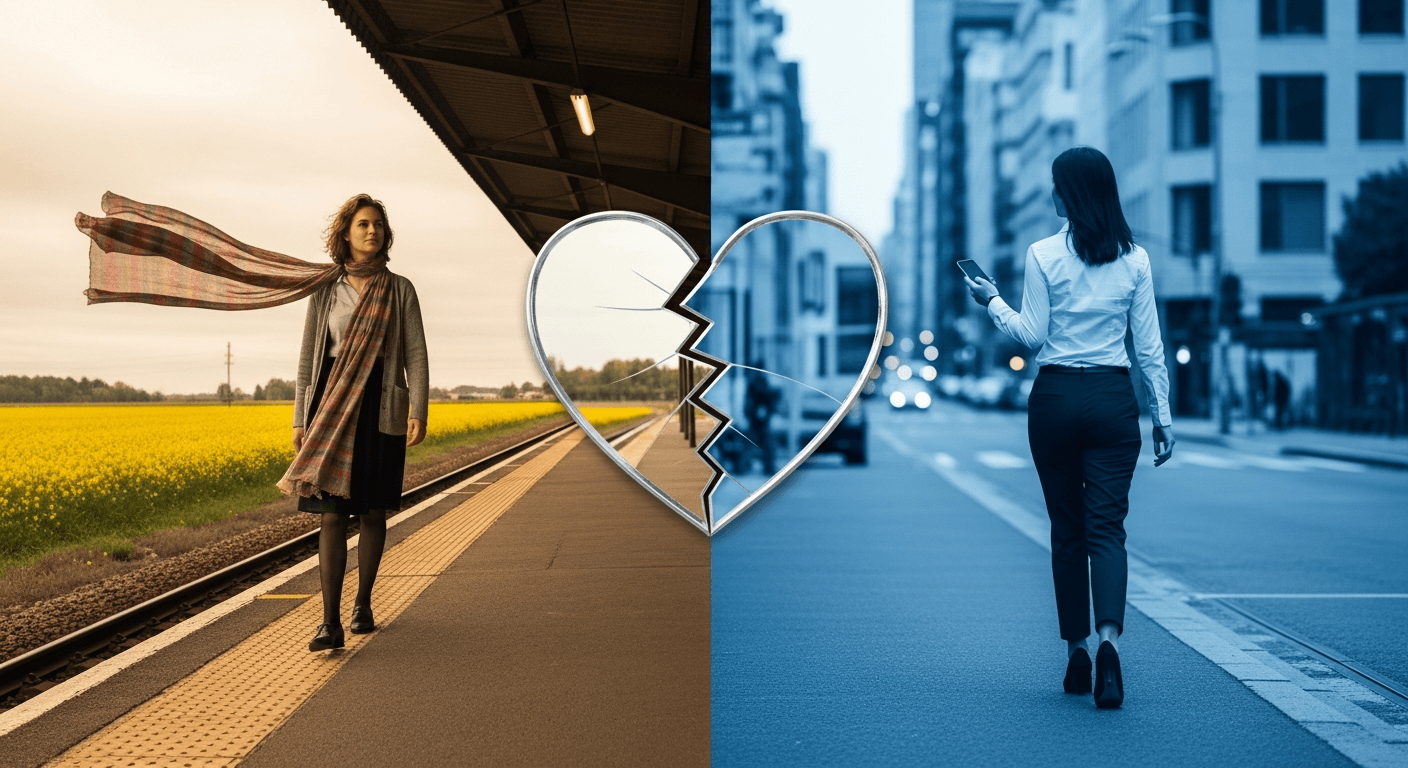

When a film becomes a ritual—screened across generations, quoted at weddings, plastered on city statues—it asks something of us beyond popcorn nostalgia. For many of us who grew up on that particular 1990s romance, the memory is a braided thing: longing, family rites, songs, and the stubborn idea that one person can rescue another from the limits life hands them.

Three decades on, I find myself impatient with that rescue fantasy.

Why the old hero feels smaller now

I still love cinema’s capacity to teach us about desire, but the archetypal hero from that era no longer sits easily with many of us who have watched the world change faster than the script did. A few reasons why modern viewers—especially women whose lives have shifted in real ways—are giving up on the old promise:

Economic and social independence. Work, mobility and finances reshape the bargaining of love. A heroine who must once have stayed within a family’s protection now has more real choices—and with choice comes a different calculus of risk and reward.Coverage of the 30th anniversary reflections

Safety and shelter are political, not personal. In many real-life contexts, choosing to abandon a family home can expose a woman to very real danger. For some, the imperfect protection of a predictable but patriarchal household looks, tragically, like a rational trade-off. The argument that one romantic man will secure a safe fallback feels less plausible today for those who have seen the costs of rebellion up close.Coverage of the 30th anniversary reflections

Romance vs. institution-building. Increasingly, the desire is less for a theatrical romantic rescue than for public systems—shelters, fair labour markets, policing and healthcare—that actually expand the space to choose. The yearning is for structural romance: institutions that let people live with dignity, not just private saviors.

Different morals for a different time. What was once forgiven as ‘charm’—persistence that borders on coercion, public spectacle that overrides consent—reads differently after decades of conversations about agency, consent and dignity.

What nostalgia still gives us

Nostalgia is not ignorance. That old romance gave millions a language to speak tenderness across class and distance. It also made public rituals—songs, trains, fields—part of how a generation learned to imagine affection. Even as I write critically, I recognise how those images shaped tenderness and courage in countless small lives. That ambivalence matters: you can revere the feeling the film created while cutting the thread to old assumptions that limited women’s horizons.

Personal reckoning

I grew up charmed by the height of that cinematic promise. I, too, once wanted the gesture—the grand chase, the last-minute leap. Over time I realised that I was romanticising a form of dependence. I now prefer politics over pageantry: give me public safety, meaningful work, and education that enlarges choice. Those are the conditions in which real love—not theatrical dependence—can flourish.

This is why I’ve quietly given up on the neat idea that a single man will make a woman’s life whole. I want the freedom to fall in love with my own life first, and then let affection be a companion to that freedom.

What filmmakers can do next

If the cinema of the 1990s taught us one grammar of love, contemporary storytellers can teach another:

- Show heroines with work, not merely poetry-writing as a hobby.

- Make consent and clear communication dramatic, not incidental.

- Portray families and institutions that both constrain and enable—nuanced, not merely obstacles to melodrama.

- Imagine public remedies (shelters, legal recourse, economic options) as part of the plot’s stakes.

Our favorite stories taught us how to feel. The next generation’s stories can teach us how to live.

Further reading and context: contemporary coverage of the film’s 30th anniversary and the continuing debates about its legacy and social meanings can be found in recent pieces reflecting on the anniversary and public moments around it, including coverage of global tributes and op-eds that interrogate the film’s political subtext.Coverage of the 30th anniversary reflections, Anniversary coverage and statue unveiling

Regards,

Hemen Parekh

Any questions / doubts / clarifications regarding this blog? Just ask (by typing or talking) my Virtual Avatar on the website embedded below. Then "Share" that to your friend on WhatsApp.

Get correct answer to any question asked by Shri Amitabh Bachchan on Kaun Banega Crorepati, faster than any contestant

Hello Candidates :

- For UPSC – IAS – IPS – IFS etc., exams, you must prepare to answer, essay type questions which test your General Knowledge / Sensitivity of current events

- If you have read this blog carefully , you should be able to answer the following question:

- Need help ? No problem . Following are two AI AGENTS where we have PRE-LOADED this question in their respective Question Boxes . All that you have to do is just click SUBMIT

- www.HemenParekh.ai { a SLM , powered by my own Digital Content of more than 50,000 + documents, written by me over past 60 years of my professional career }

- www.IndiaAGI.ai { a consortium of 3 LLMs which debate and deliver a CONSENSUS answer – and each gives its own answer as well ! }

- It is up to you to decide which answer is more comprehensive / nuanced ( For sheer amazement, click both SUBMIT buttons quickly, one after another ) Then share any answer with yourself / your friends ( using WhatsApp / Email ). Nothing stops you from submitting ( just copy / paste from your resource ), all those questions from last year’s UPSC exam paper as well !

- May be there are other online resources which too provide you answers to UPSC “ General Knowledge “ questions but only I provide you in 26 languages !

No comments:

Post a Comment